Hurdles in Child Imaging

The main hurdle is that they are small and energetic as always. Motion and motion related artifacts are the biggest challenges in child imaging. The high heart rates and rapid breathing is an inevitable factor causing motion artifacts. Another big concern in pediatric CT imaging remains exposure to radiation. The adverse events from anesthesia also preventing the imaging in Neonates with complex Congenital Heart Disease (CHD).

Quality Scans at Lower Dose

The objective of the whole technique is to get images from the scanning procedure to achieve sound diagnosis in child CHD. Evaluation involving complex anatomy of the body such as the heart, liver, spine & individual blood vessels. The cross sectional details in pediatric imaging are extremely small that demands for good quality imaging. At the same time, radiation dose in this category is a primary concern. Pediatric CT imaging means you have to keep the radiation doses at a bare minimum.

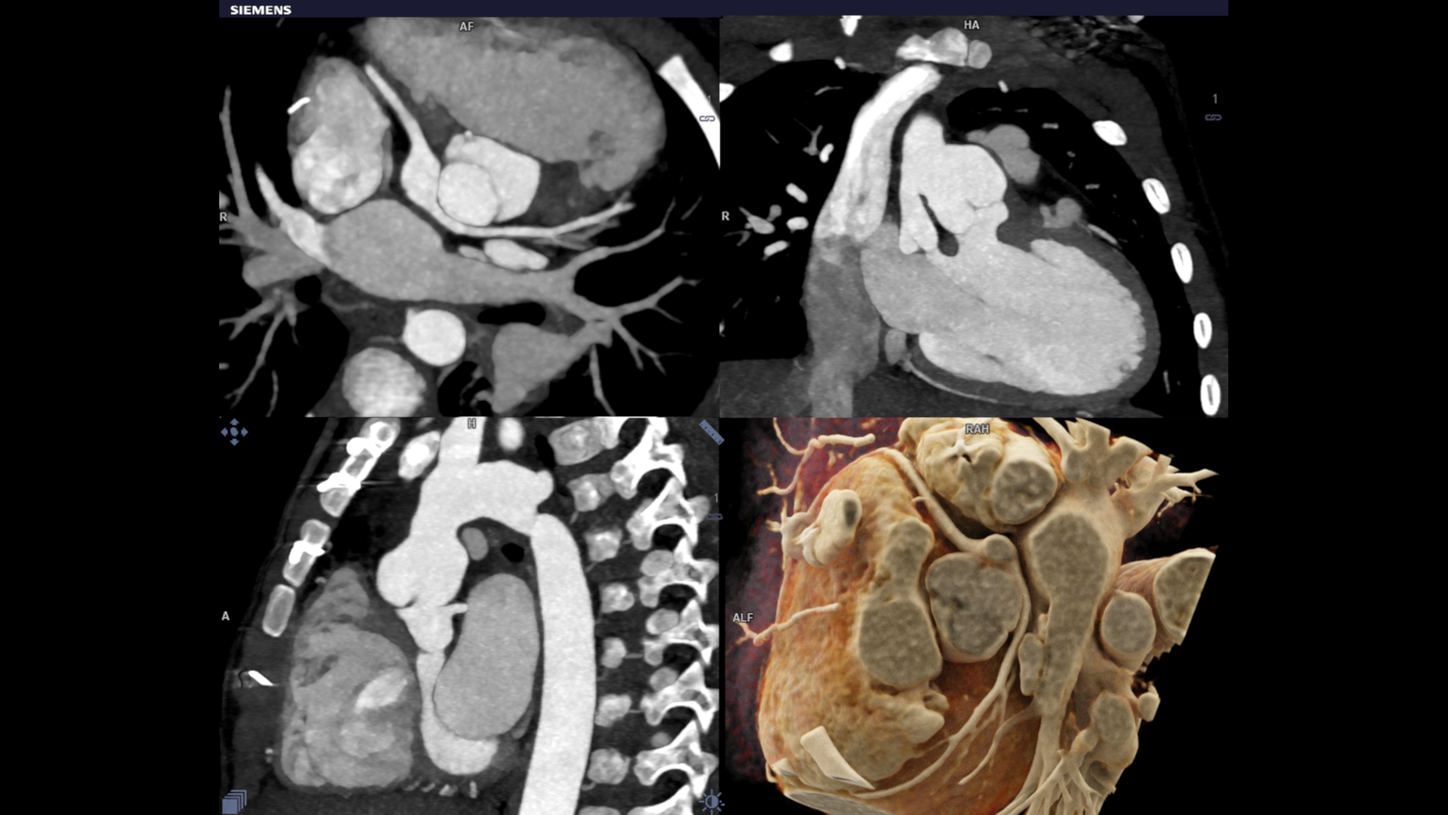

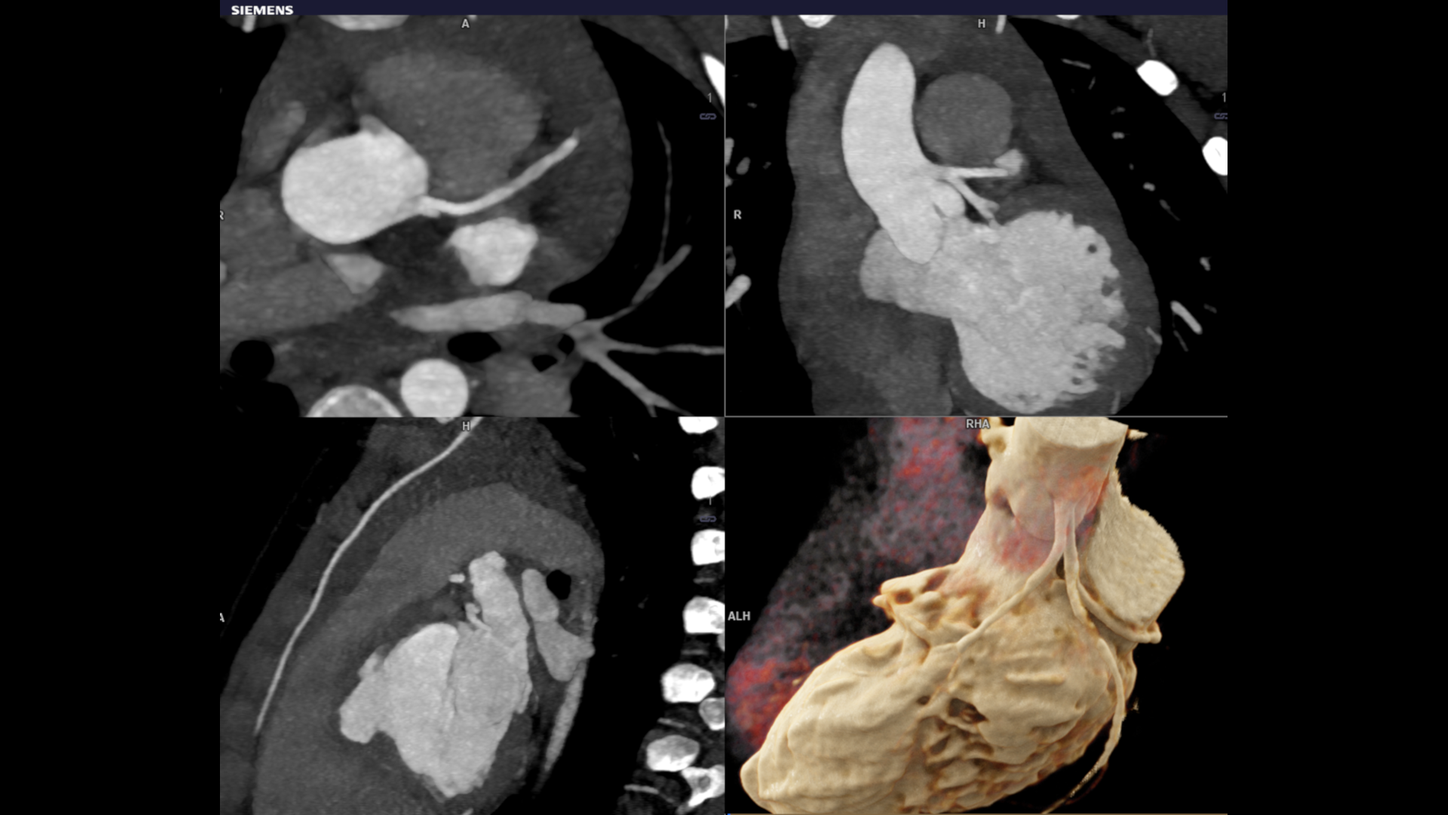

Dual source turbo flash spiral the combination of two sources, a high table feed (increasing scan speed up to 737 mm/s), rapid acquisition (0.25 s) and ultra-fast data transmission, and hence CT scanner makes its high temporal resolution (66 ms ). It enables extremely short scan times with very low radiation doses. Iterative reconstruction technique ADMIRE help to generate high quality images from low dose high noisy data set.

Conclusion

CHD is the most common congenital anomaly and causes more deaths in the first year of life than any other birth defect. Most cases of CHD require surgery or interventional procedures to restore the heart’s normal function. This recent technological improvement has been attributed to better imaging and improved understanding of the anatomy of CHD. Cardiac surgeons and radiologists collaborate in the treatment of children with Congenital Heart Disease (CHD). Faster imaging produces 3D reconstructions and models are to be used as planning tools for surgery. Turbo flash imaging is an excellent choice for the clinical evaluation of CHD especially as the imaging needs to be performed in free breathing and without sedation. Iterative reconstruction technique helps to create quality images from low dose noisy data.

The outcomes by Siemens Healthineers customers described herein are based in results that were achieved in the customer’s unique setting. Since there is no ”typical” hospital and many variables exist (e.g. Hospital size, case mix, level of IT adoption), there can be no guarantee that other customers will achieve the same results.

References

1. Chan J, Khafagi F, Young AA, et al. Impact of coronary revascularization and transmural extent of scar on regional left ventricular remodelling. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1608-17.

2. Gutberlet M, Fröhlich M, Mehl S, et al. Myocardial viability assessment in patients with highly impaired left ventricular function: Comparison of delayed enhancement, dobutamine stress mri, end-diastolic wall thickness, and ti201-spect with functional recovery after revascularization. Eur Radiol 2005;15:872-80.

3. Mahrholdt H, Wagner A, Parker M, et al. Relationship of contractile function to transmural extent of infarction in patients with chronic coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:505-12.]

4. Einstein AJ, Berman DS, Min JK, et al. Patient-centered imaging: shared decision making for cardiac imaging procedures with exposure to ionizing radiation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1480-9.

5. Meyer GP, Wollert KC, Lotz J, et al. Intracoronary bone marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: eighteen months’ follow-up data from the randomized, controlled BOOST (Bone marrow transfer to enhance ST-elevation infarct regeneration) trial. Circulation 2006;113:1287-94.

6. Schächinger V, Assmus B, Britten MB, et al. Transplantation of progenitor cells and regeneration enhancement in acute myocardial infarction: Final one-year results of the TOPCARE-AMI trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:1690-9.

7. Leipsic J, Abbara S, Achenbach S, Cury R, Earls JP, Mancini GJ, et al. SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary CT angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. Journal of cardiovascular computed tomography. 2014;8(5):342-58.

8. Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, Gitter M, Sutherland J, Halamert E, et al. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;52(21):1724-32.

9. McCrindle BW, Li JS, Minich LL, et al. Coronary artery involvement in children with Kawasaki disease: risk factors from analysis of serial normalized measurements. Circulation. 2007.

10. Manlhiot C, Millar K, Golding F, McCrindle BW. Improved classification of coronary artery abnormalities based only on coronary artery z-scores after Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010.

11. Kato H, Sugimura T, Akagi T, et al. Long-term consequences of Kawasaki disease. A 10- to 21-year follow-up study of 594 patients. Circulation. 1996.

12. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004.

13. Lee DC, Simonetti OP, Harris KR, et al. Magnetic resonance versus radionuclide pharmacological stress perfusion imaging for flow-limiting stenoses of varying severity. Circulation. 2004.

14. Tacke CE, Kuipers IM, Groenink M, Spijkerboer AM, Kuijpers TW. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for noninvasive assessment of cardiovascular disease during the follow-up of patients with Kawasaki disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011.