The development of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an exciting story of innovation spanning four decades – if not several centuries – and two Nobel prizes. But the fact that MRI scanners are now used in patient care all over the world is also thanks to industrial research and development.

Photos: Gettyimage/Siemens MedMuseum

Illustration: David Hänggi

A mathematician from the time of Napoleon

Where to start? Like many technological innovations, it’s impossible to pin down the precise birth of MRI. If you prefer to go way back, a good place to start is Napoleonic France, where Jean-Baptiste Fourier developed the mathematical process that bears his name: the Fourier transform. Even though Fourier naturally wasn’t familiar with atomic nuclei, electromagnets or even electrical current, his transform is used as the basis for calculating MRI images to this day.

Nikola Tesla in his laboratory.

Back then a genius, today a unit of magnetism

A

century later, another figure with a legitimate claim to having fathered MRI

was the Serbian electrical engineer and inventor Nikola Tesla. Tesla was an

all-round genius, filing around 300 patents in 20 countries as well as speaking

at least eight languages fluently. In addition to many other discoveries, he

described how magnetic fields arise and what properties they have. That brought

him immortality: his last name is now used as a unit representing the strength

of magnetic fields. Most of the modern MRI scanners in hospitals are 1.5-tesla

units.

Nobel prize for magnetic resonance

The most important basic research for the future development of MRI was probably done by the Swiss physicist Felix Bloch and his US peer Edward Purcell. They showed that atomic nuclei could absorb radio frequency waves if these were at the same frequency the nuclei were vibrating at. From that point, this phenomenon was known as magnetic resonance. Bloch and Purcell were awarded the 1952 Nobel Prize in physics for their discovery, made independently of each other.

The first wooden MR research laboratory, Erlangen, 1979.

Use on living organisms - and another Nobel prize

In

the two decades following the Nobel Physics Prize, magnetic resonance

technology was used for spectroscopic purposes in materials science, with the

radio waves reflected after magnetic “activation” of a material giving insights

into the constituent components of the material under investigation. The only

thing missing for the technology to be used in medical diagnostics was a way of

assigning the signal spatially. The additional magnetic fields, so-called

gradient fields, necessary to do this were introduced by US chemist Paul

Lauterbur in 1973. From 1974 onward, British scientist Peter Mansfield, developed the mathematical methods, based on Fourier, enabling radio frequency

signals to be converted into image signals. Thirty years later, in 2003,

Lauterbur and Mansfield were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Raymond Damadian, who in the 1970s had made a substantial contribution to the

establishment of MRI for living organisms and in 1977 produced the first image

of the human body, was overlooked by the Nobel Committee.

MR image of a bell pepper. 1980.

MRI let loose in Germany - on a pepper

In

the early 1970s, MRI was a highly experimental procedure that as yet had

nothing to do with medical care. That changed later in the decade as medical

technology companies started to refine it into a usable diagnostic method. One

of the global pioneers was Siemens in Erlangen, which remains one of the market

and innovation leaders in this technology to this day. In 1978, a prototype

Siemens MRI scanner produced the first image in Germany – of a bell pepper. In

March 1980 Alexander Gassen, a physicist at Siemens, put himself in the tube

for eight minutes for an image of his cranium. The first full-body scan

followed later the same year.

Giant tubes rolled out

In

1983, things got really exciting in terms of the clinical application of MRI, with

several things happening at the same time. Schering AG filed a patent for the

contrast agent Gadolinium-DTPA, which would become indispensable from the late

1980s on. In January 1983, Siemens also installed its first clinical MRI

machine as a prototype at Hanover Medical School (MHH). More than 800 patients

were subsequently scanned as part of clinical trials, lying on a patient bench

made of wood. In August 1983, the world’s first commercial MRI machine – a

Siemens MAGNETOM – went into operation at the Mallinckrodt Institute in St.

Louis, Missouri. Germany’s first MAGNETOM was installed at the Armin Kühnert

radiology practice in Dietzenbach. Over the next few years around 150

first-generation machines were rolled out, primarily in the United States and

Japan. The magnetic fields used by these scanners started at 0.35 tesla before

progressing to 0.5 tesla, and then all the way to 1.5 tesla. They looked like

giant washing machines and required a huge amount of space: around 140 square

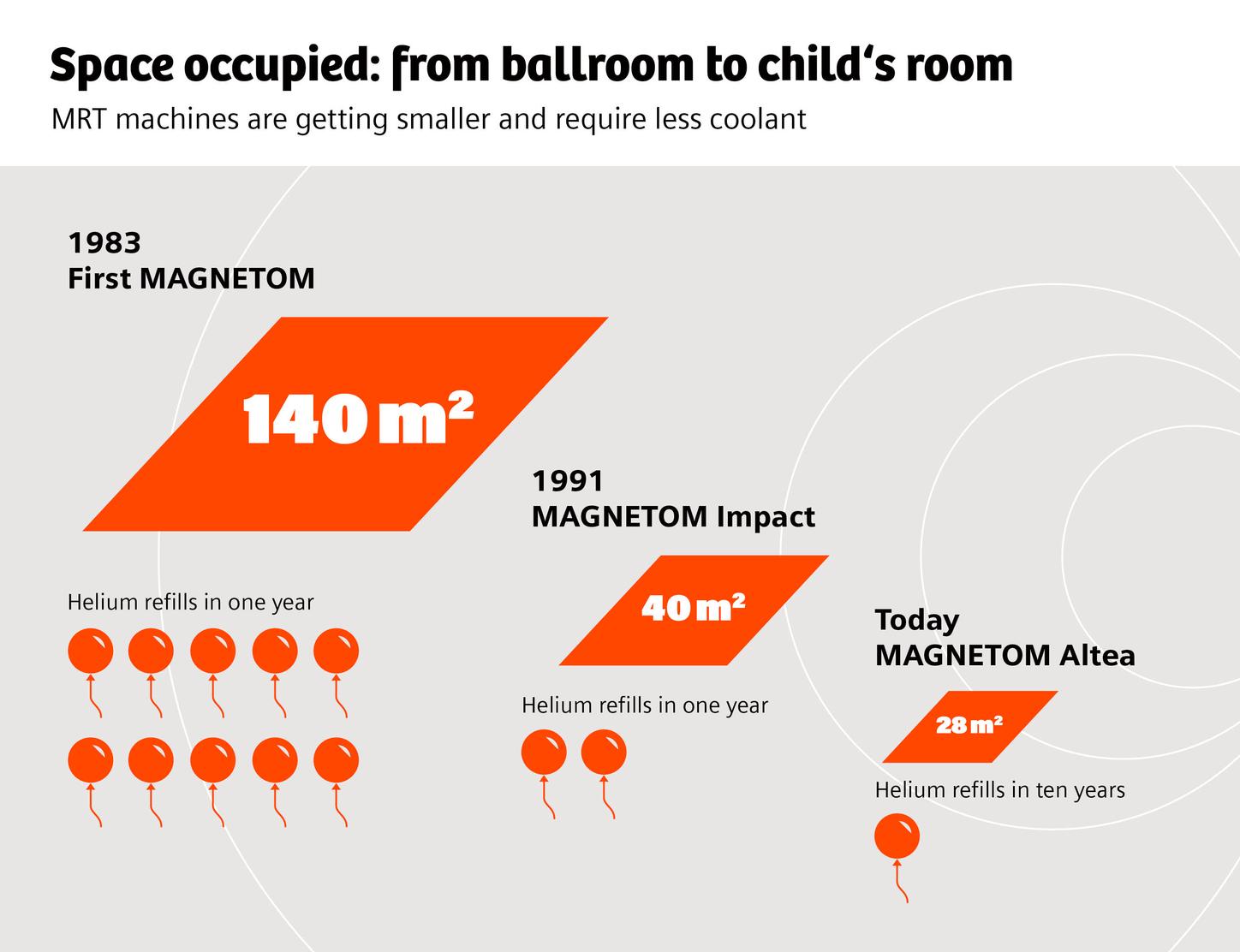

meters for the 1.5-tesla version of the MAGNETOM.

Examination with the first MAGNETOM, 1983.

Finding its way into routine

In

the decade following the installation of these first machines, MRI technology

became increasingly user-friendly. Thanks among other things to more effective

shielding of the superconducting magnets, both the space and the number of

helium refills required decreased, enabling many more facilities to install an

MRI scanner. MRI also moved into other areas of application. An important

milestone at the end of the 1980s was ECG gating, linking MRI measurements to

an ECG taken during the scan. This made it possible to limit scanning of the

heart to only a very specific phase of the cardiac cycle, eliminating the

otherwise unavoidable blurring caused by the heart’s beating. It marked the

start of MRI’s triumphant advance in cardiology.

More powerful, more usable, and less time-consuming

In

the course of the 1990s and 2000s, medical technology manufacturers constantly

refined MRI technology to the limits of what was technically possible.

Performance continued to improve, all the way to the ultra-high field systems

with magnetic fields of 7 tesla and more that were available from the turn of

the millennium. There were also advances in coils: technologies such as the

total imaging matrix enabled more comfortable and convenient – and above all

quicker – full-body scans. At the same time it was also possible to enlarge the

opening of the MRI scanner from a narrow 60 centimeters to 70 centimeters, much

more pleasant for patients. Working procedures were also greatly optimized, and

user-friendliness improved as many steps that had previously had to be set

manually were automated.

A Milestone reached

The

last big milestone in the history of the MRI was reached in 2010 when Siemens

Healthineers presented a hybrid MRI and positron emission tomography (PET)

scanner in a single unit. This innovation married the MRI’s millimeter-precise

soft tissue anatomy capabilities with PET’s molecular imaging – opening up

whole new perspectives, not least in oncology.